Medieval Bound is a study notebook on fifteenth-century Europe, approached through maps, representations, and texts that allude to the imaginary of the period. From the Aegean islands to the ports of the Mediterranean, crossroads of memory in the humanist era, it brings into view the cultural landscapes of its time. Among the witnesses of that age is the Florentine cartographer Cristoforo Buondelmonti.

European and Mediterranean

Fifteenth Century

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, the Mediterranean constituted a complex theatre of power, commerce, and conflict. Italian cities such as Florence, Venice, and Genoa operated extensive mercantile networks, while the islands and the eastern coastlines were governed by local polities and religious–military orders, such as the Knights Hospitaller, and were threatened both by pirate and corsair incursions and by the military and political expansion of the Ottoman Empire.

Within this context, figures such as Cristoforo Buondelmonti moved between scholarly circles, libraries, and Mediterranean ports, gathering geographical, political, and cultural information which they subsequently translated into maps and manuscripts, thereby contributing to the development of cartographic knowledge and to the humanist networks of learning of the fifteenth century.

Cristoforo Buondelmonti

"Cristoforo Buondelmonti, a man of the science of cosmography, of the studies of geography as well as of all human literature; extroverted in dialectics, brilliant in wit and able to speak three languages."

(Poccianti M., Catalogus illustrium scriptorum Florentinorum)*.

The Buondelmonti Family

The Buondelmonti were an ancient and renowned family in the history of medieval Florence. Their origins and their fate, like those of several noble families of the period, are inextricably bound to the political, economic, and social history of the Tuscan city.

Recent historiography has shed light on a number of Florentine families in the late medieval period, as well as on the economic and matrimonial dynamics that, in certain cases, determined their extinction.

The destiny of the Buondelmonti family belongs to this latter category. Although one of the wealthiest and most important families, and long protagonists of civic life, over the centuries they gradually moved towards definitive decline, culminating in extinction in 1774 with the last heir, Francesco Gioacchino, son of Giuseppe Maria Manente.

As holders of estates, substantial properties, and possessions both within the city and across the Florentine contado—with parish churches and ecclesiastical benefices generating income—the Buondelmonti, in addition to being among the principal lay landowners, were able to exercise rights of patronage accompanied by significant revenues.

The Buondelmonti family became notorious as a result of a discord that occurred in 1215 involving Buondalmonte de' Buondelmonti, who was killed for having failed to honour a marriage promise. The ensuing affronts led to acts of revenge in public spaces and gave rise to a political division within the city, splitting it into two factions: the Guelphs, with the Buondelmonti as supporters of the papacy, and the Ghibellines, aligned with the Emperor.

Among the chroniclers of this discord were Dino Compagni, Giovanni Villani, and Dante Alighieri, who, in the Divine Comedy, conferred both notoriety and unpopularity upon the Buondelmonti, attributing to them responsibility for internal division as well as for civic strife, the beginning of Florence's decline, and the end of peace for its inhabitants—a crisis in which he himself would later be entangled:

"O Buondelmonte, how ill thou fleddest his bride

at others' counsel! Many would be glad, who now are sad,

if God had granted thee to Ema the first time

thou camest to the city…"

(D. A., Paradiso, XVI, 140–145)

In these verses, Dante underscores that had the first ancestor of the Buondelmonti, upon arriving in Florence, plunged into the torrent of the Ema and drowned, the city would not have fallen victim to fatal internal struggles.

This episode nonetheless highlights both the influence and the power exercised by the Buondelmonti within the city, for they are placed by the supreme poet in his Comedy in Paradise, in the Heaven of Mars, among the forty ancient and honourable families of Florence.

Cristoforo Buondelmonti: Early Years and Studies

The son of Ranieri Buondelmonti, Cristoforo was born in Florence in 1385 and grew up in a city of exceptional vitality, progressive in outlook and animated by a degree of intellectual energy and creative flair scarcely to be found elsewhere in Europe.

It is certain that the young Buondelmonti attended the Circle of Santo Spirito, where he developed an interest both in classical authors and in geography, cartography, and ancient pre-Christian architecture. Nevertheless, he chose to pursue an ecclesiastical career, undoubtedly aware—beyond any sense of vocation—that the administration of a parish within the city or of a pieve in the contado would provide a secure annual income. This path he followed at the Church of Santa Maria sopra l'Arno in Florence (a church no longer extant), under the patronage of the Buondelmonti family, until his appointment to the title of archpriest.

The codices of Ptolemy's Geography, seen and discussed at the Circle of Santo Spirito with Niccolò Niccoli and Guarino da Verona, undoubtedly catalysed the young humanist's interest in ancient, though not so distant, Greece, giving him the impetus to embark upon a voyage of exploration and documentary recording of the perilous archipelago of the Aegean Sea.

The cartographer departed from Florence in the spring of 1414, embarking perhaps at Ancona or from Venice, which possessed a greater number of galleys bound for Greece. It is highly probable that Rhodes, as a place of residence and point of reference, had already been decided upon some years earlier at home, having been identified by the Florentine circle. The geographical area of interest had been largely under Western domination since the thirteenth century.

Residing on the island of Rhodes, at that time governed by the Knights Hospitaller of Saint John, he benefited from their powerful fleet, which guaranteed him safe travel in perilous times and allowed him to move while always having a protected harbour upon which to rely.

From as early as the thirteenth century, bankers, merchants, and traders from various Florentine families—including the Bardi, the Albizzi, the Peruzzi, the Strozzi, and above all the Acciaioli, to whom Buondelmonti was related—were present on Rhodes; these families held commercial funds and properties there, as well as in Epirus. The island also possessed a centre for the study and research of Greek classical texts, smaller than others but nonetheless important for learning and discussion, and more than sufficient as a point of departure.

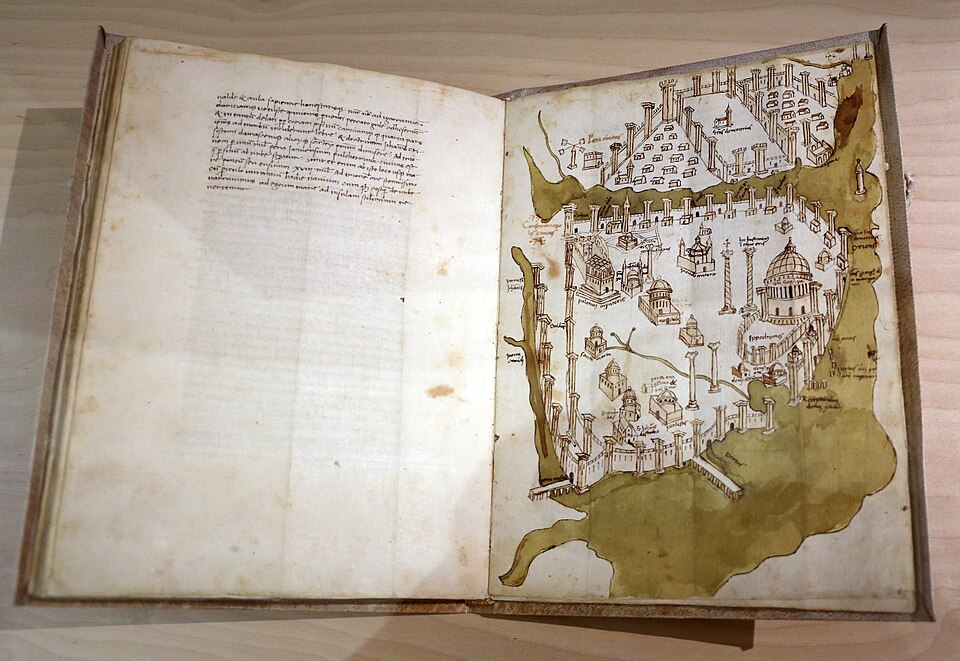

The possibility that he returned to Florence on several occasions cannot be excluded, as attested by many works preserved in various manuscript codices signed by Buondelmonti and dispersed in libraries throughout Italy and Europe, bearing dates that extend to the end of the fifteenth century. Scholars agree that he stayed on the island of Crete on at least three occasions, an area certainly much larger than the island of Rhodes, albeit less conducive to the cartographer's projects and to serenity in his work; this, together with his documented time spent in Constantinople—where he is thought to have resided on several occasions (Weiss, 1964, p. 106; Van der Vin, 1980, p. 135)—constituted decisive stages in view of the importance of his codices.

Principal Works

Buondelmonti's renown as a cartographer is founded primarily upon three manuscripts that are without doubt attributed to him: the Descriptio Insulae Candiae or Cretae (1416–1422), the Nomina Virorum Illustrium (1423), and above all the Liber Insularum Archipelagi (c. 1419–1430). The latter work was rewritten on four occasions (the definitive edition dating to 1430) and survives in a long and elegant version and in a shorter one, both in Latin, as well as in a third version in the Venetian dialect and a fourth in the Marchigian dialect.

The Descriptio Insulae Cretae constitutes the first model codex, in which the cartographer describes the island of Crete. It was produced after 1416 at the request of the Florentine patron Niccolò Niccoli, with whom he was in contact by correspondence. The third work, the Nomina Virorum Illustrium (The Lives of Illustrious Men), was composed at the request of Janus of Lusignan (Genoa, 1375 – Nicosia, 25 June 1432), King of the island of Cyprus, in light of the success and circulation of Buondelmonti's works already achieved after only a few years of his presence in the Greek archipelago.

Patrons and Political Context

The second work, the Liber Insularum Archipelagi, was commissioned for Giordano Orsini, a highly influential cardinal belonging to one of the most powerful Roman families and of the surrounding castles, together with the Colonna, the Savelli, the Annibaldi, and the Caetani—families that, from the thirteenth century onwards, dominated the political landscape through alliances, peaces, rivalries, and wars among themselves.

A branch of the Orsini family, during this period, by aligning itself with the policies of the Roman pontiffs, secured new territories and castles in the region, and Giordano Orsini was one of the key cardinals at one of the most complex moments in the history of the Roman Curia.

A man of the fifteenth century, Orsini embodied the controversial spirit of his age, ruthless and power-hungry yet also a learned humanist with a passion for manuscripts and ancient codices; he acquired many in order to enrich his library, and Buondelmonti was among his contacts. Towards him, Orsini did not merely act as a patron to be protected and supported financially, but also regarded him as a trusted agent overseas, in a borderland that was dangerous and in need of defence.

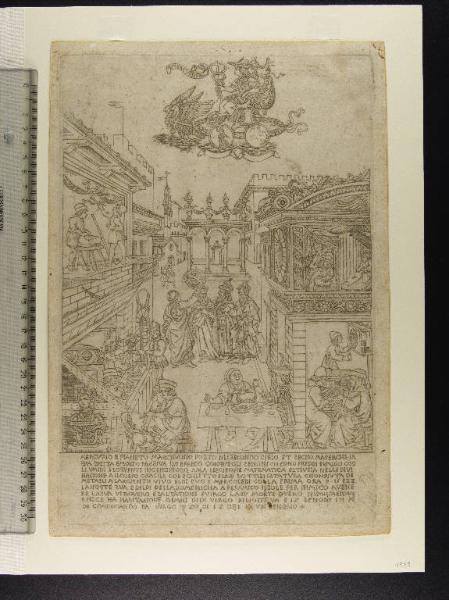

The Liber Insularum Archipelagi concerns the entire Greek archipelago. Within it, in addition to descriptions of all the islands and of the solemn Mount Athos, Buondelmonti recorded the few cities he deemed most significant for his time, with drawings and commentaries. He was always very brief on Gallipoli, treated Athens and its ruins only in passing, whereas Constantinople, which deeply impressed him, is presented with figures, illustrations, and a map that would become an absolute point of reference as an image of the medieval city, and moreover remains the earliest surviving map of the city of Istanbul prior to the Turkish conquest of 1453.

From the very beginnings of modern archaeological research in the Aegean, the descriptions and maps of the various islands recorded by Cristoforo Buondelmonti have often represented the point of departure for any scholar interested in reconstructing the history of a given island and in assessing the state of preservation of its monuments.

His investigations into antiquities and his rigorous methods of compilation represent the first expressions and the earliest efforts inspired by that forma mentis to which early fifteenth-century Florentine humanism adhered.

Cristoforo Buondelmonti cultivated interests in archaeology and epigraphy, devised a new literary genre, and was a highly skilled procurer of Greek manuscripts, being the first to have brought back classical authors such as Aristotle, Plato, Vitruvius, Cicero, Libanius, Plutarch, Terence, Plautus, Ptolemy, and Pliny the Elder, as well as the codex containing the then unknown Hieroglyphica of Horapollo, the first treatise devoted to the interpretation and understanding of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Diplomatic Role and Final Years

As his historiography and chronicles show, Buondelmonti, during his life in Greek lands, conducted himself as a skilled diplomat, presenting himself differently according to his interlocutors: to Italian clerics as a Florentine archpriest, to Westerners as a Latin presbyter, and to Eastern Christians as deacon of the island of Rhodes, thus also serving as confidant and chaplain of the Knights of Saint John.

He also identified himself as a citizen of Florence during commercial negotiations, while the close familial ties linking him to highly influential families in the archipelago, such as the Acciaioli, the Tocco, and the Spada, were frequently employed in moments of tension or danger among the many islets of the Aegean Sea.

He was certainly a man who acted on behalf of the Latin Curia as an agent in rebus, interlocutor, and diplomat. Not by chance, in the book-list of illustrious men and women, at the express request of the patron, Dominus King Janus of Lusignan, his name also appears.

Regarding Buondelmonti and his presumed death, much research has been conducted, and doubts remain. In June 1430, he is documented in Rhodes, the latest date attesting to his life. Two acts record the presence of "Cristoforus Bondalmontibus" titled as dean of the cathedral church of Rhodes, by papal bull of Martin V (born Oddone Colonna).

Although the deanship carried very low remuneration in Rhodes, it was highly honourable, being the second-ranking dignitary of the island after the Archbishop of Colossi. The last official act attesting to his presence on the island and to his life is dated 24 June 1430.

The exact date of death of the Florentine humanist remains unknown, though several scholars maintain, with due caution, that it may have occurred during the violent outbreak of the Black Death that struck Rhodes in 1431, as recorded by contemporary chroniclers and later sources. The possibility that the Florentine agent survived to witness the fall of Constantinople in 1453 cannot be entirely excluded, considering that contemporary and early subsequent insertions and updates, attributed to Cristoforo Buondelmonti, may have been made by him in person.

Alessandro Bellucci

Footnotes / References

*Poccianti, Michele. Catalogus scriptorum Florentinorum omnis generis, quorum, et memoria extat, atque lucubrationes in literas relatae sunt ad nostra vsque tempora. Florence: apud Philippum Iunctam, 1589.

**Santa Maria dei Bardi, popularly known as Santa Maria Sopr'Arno, was one of the oldest parish churches of Florence, attested from 1181 and rebuilt in the thirteenth century with the support of the Bardi family. Located on the Arno, it was suppressed in 1785 and demolished in 1869 to allow the expansion of the lungarni. Artistic evidence and its memory survive in a painting by Telemaco Signorini.

Siniscalchi, S. "Gli orientamenti delle ricerche storico-cartografiche e cartografico-storiche in Italia. Una rassegna bibliografica ragionata degli ultimi trent'anni attraverso gli indici delle principali riviste geografiche italiane." In Storia della cartografia e Cartografia storica, edited by A. Guarducci and M. Rossi, Aspetti teorici e metodologici, 1987–2016, Geotema 58, Anno XXII (September–December 2018): 8–16.; Da Bisticci, V. Le vite, edited by A. Greco, vols. 2. Florence: Istituto Nazionale di Studio sul Rinascimento, 1970–1976.; Bertozzi, T. I viaggi, i traffici e le scoperte del fiorentino Cristoforo Buondelmonti nella Grecia del XV secolo. Consultancies by M. S. Mazzi. PhD dissertation, University of Ferrara, Department of Humanities, XVI cycle, Ferrara, 2004, 280 pp. (Research preserved at Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Cod. TDR 2004 3368).;, Radif, L. "Cristoforo Buondelmonti e Penia di Rinuccio Aretino." Interpres: Rivista di studi quattrocenteschi, Miscellanea, 28 (Rome, 2009): 222–236.Van Spitael, M. A., Cristoforo Buondelmonti, Descriptio Insule Crete et Liber Insularum, Cap. XI: Creta. Hèrakléion Krètès, 1981, pp. 345 + XXII pl.;, Van der Vin, J. P. A. Travellers to Greece and Constantinople: Ancient Monuments and Old Traditions in Medieval Travellers' Tales, Vol. I, Chapter VII, Geographers 2. Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul. Printed in Belgium: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 1980, pp. 133–149.Gerola, G. "Le vedute di Costantinopoli di Cristoforo Buondelmonti." Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici III (1931): 249–279.;Litta, P. Le famiglie celebri italiane, Tav. I–XII, s.v. Buondelmonti. Milan, 1819. Bec, C. Cultura e società a Firenze nell'età della Rinascenza. Rome: Salerno Ed., 1981.; Weiss, R. "Un Umanista Antiquario: Cristoforo Buondelmonti." Lettere Italiane 16, no. 2 (1964): 105–116.; Perreault, A. "Le Liber Insularum Archipelagi: cartographier l'insularité comme outil de légitimation territoriale." Memini 25 (2019). https://journals.openedition.org/memini/1392 . DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/memini.1392

BUONDELMONTI C., Liber Insularum Archipelagi, libera in rete, https://openmlol.it/media/cristoforo-buondelmonte/liber-insularum-arcipelagi-christoforo-buondelmonti/1294937

Representations of some Aegean islands by Cristoforo Buondelmonti, taken from the Liber Insularum Archipelagi (1422).

Images taken from: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Geography and Cartography in the Fifteenth Century

Geography is the treatise by Claudius Ptolemy which, in the second century CE, defined the mathematical representation of the Earth. This work, rediscovered in the fifteenth century, opened the way to cartography and to mathematical geography within Humanism.

Below is the Map of Greece, from the edition by Francesco Berlinghieri (1482, manuscript held at the library of the Accademia della Crusca). The map of Ptolemy's Ecumene, shown in detail, is reproduced from Nicolaus Germanus, Cosmographia Claudii Ptolomaei (before 1467). It originates from the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 30.4, fol. 70v (part.). Extracted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

"Here at the border, the leaves fall,

and though all the neighbours are barbarians

and you, you are a thousand miles away,

there are always two cups on the table."

(Dinastia Tang, Talas, Du Huan 771 d.C.)

Between 1400 and 1472, it is estimated that only a few thousand maps were in circulation; between 1472 and 1500, approximately 56,000. After one hundred years, by the end of the sixteenth century, more than a million could be counted (Broc, 1996, p. 42).

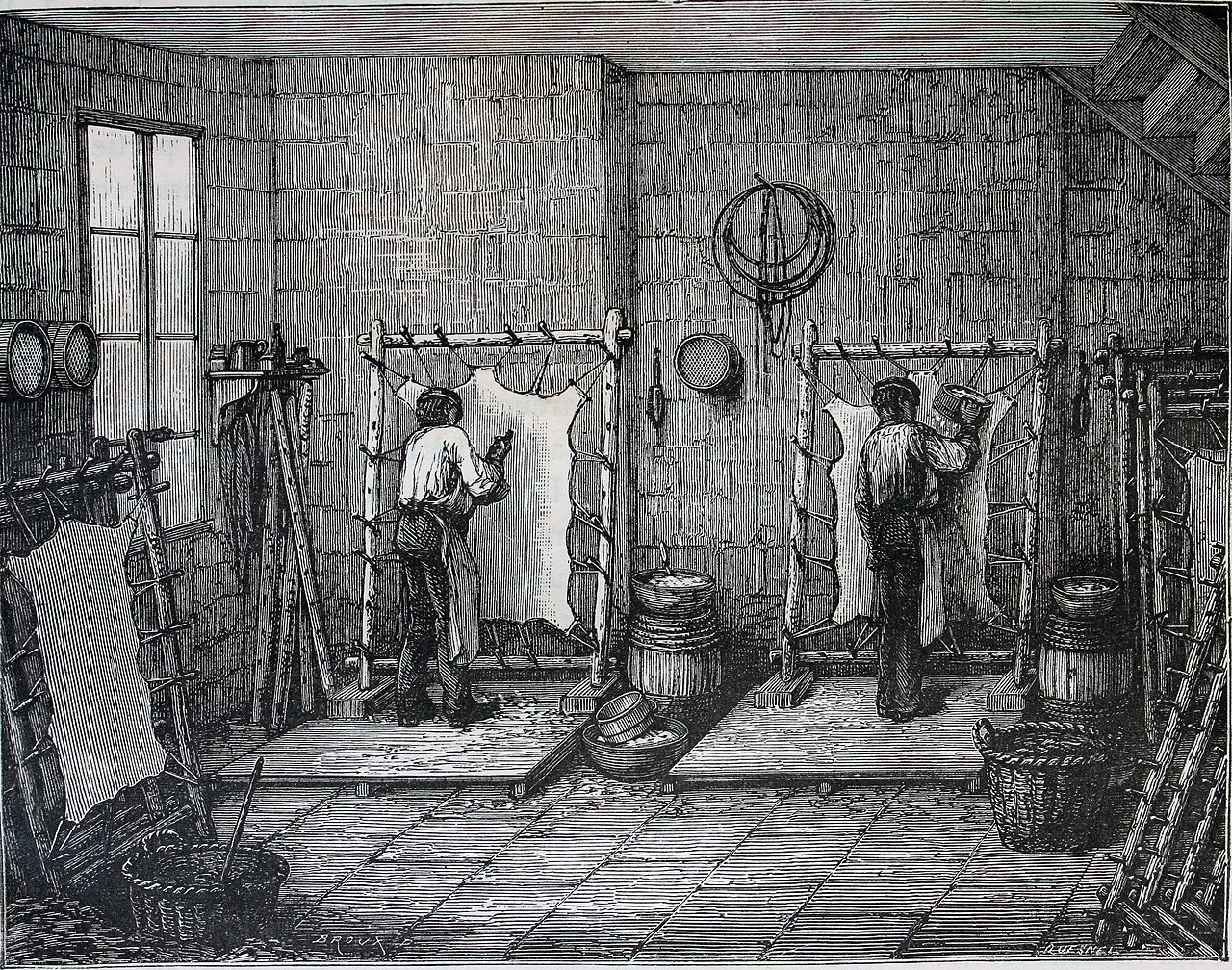

The disproportionate numerical increase from the beginning to the end of the sixteenth century was partly caused by the progressive literacy promoted by the Italian humanist movement, which expanded the dissemination of texts and thereby generated both the development and the demand for economical hemp-fibre paper for writing texts, manuscripts, and codices, as opposed to the customary parchment. Decisive was also the introduction (around 1450) and consolidation of movable type printing, fundamental in the multiplication of manuscripts, thanks to the process devised in Mainz by the goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg, which allowed texts of any nature to be published more quickly, economically, and in larger quantities. The overall dynamics of this enterprise in turn created a new economic sector: publishing.

The first book printed by Gutenberg using the new technique was the 42-line Bible (1453–1455). Within three years, 180 copies were produced, 48 of which have survived to the present day. Forty copies were printed on parchment and 140 on hemp paper. This model subsequently spread throughout Europe, and by 1480 there were already 110 printing presses on the continent, 50 of which were in Italy.

The parchment page was very costly, required considerable time to produce, and, moreover, containing a large amount of collagen, created a surface particularly sensitive to environmental conditions, humidity, and sudden climatic changes, which caused wrinkles and shrinkage—an issue of no small consequence for maps and charts.

Sino-Arabic paper proved decisive, due to the easy availability of the raw material for the sheets, increasingly becoming the medium through which knowledge and information were transmitted more rapidly, thereby promoting wider dissemination and extending the progress and growth of science and culture across much of Western Europe. The know-how for its manufacture derived from regions with an Arabic tradition, where the technique had been mastered for many centuries.

In 751 CE, the Persian dynasty of the Abbasid Caliphate, together with numerous Tibetan contingents led by Emperor Tride Tsuktsen, fought against the armies of the Chinese Tang Dynasty (唐朝, Tángcháo, 618–907), defeating them in a major engagement along the great river and in the area around the city of Talas (today in Kazakhstan), known as the "Battle of Talas" (Hoberman, 1982, pp. 26–31).

The event had enormous significance for the geopolitical influence of the Abbasids, marking the conquest of the Central Asian regions of Transoxiana, including the historic region of Sogdiana (comprising present-day southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan), whose language had served as the lingua franca of commerce, at least until the Arab conquest. The Sogdians were the main agents of that cross-fertilisation of ideas and traditions which served as a bridge between civilizations (Foltz, 2013, pp. 23–29). It was a rich and learned region, with prosperous and lively cities such as Balkh and Baykand; Bukhara, wealthy and renowned for philosophical and intellectual studies; the legendary Afrasyab, famed for its painting and arts (later completely destroyed by Genghis Khan in the thirteenth century); and Samarkand, the capital—an influential and multifaceted city, an economic hub and a key node of the Silk Road, the network linking Asia and Europe. This route facilitated the exchange not only of goods, both precious and ordinary, but also of ideas and new technologies. Merchants and guides were largely Iranian-speaking and adhered to various religions, including Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Manichaeism (Foltz, 2013, pp. 23–29).

Following the Battle of Talas, several thousand Chinese prisoners of war remained in captivity, some of whom knew secret techniques concerning gunpowder, papermaking, and silk production. Moreover, Du Huan, a Chinese narrator and historian, who had been captured by the Abbasid army at Talas, on his return to China published his travel writings, documenting that Chinese crafts such as silk weaving and hemp processing were practiced by the Tang prisoners, many of whom were forced to reside in Abbasid-controlled territory, some deported as far as Damascus (Hyunhee, 2012, p. 25).

The technique of producing paper from vegetable fibres, predominantly hemp, spread rapidly outside Chinese spheres of influence, being highly sought after from the outset. With the growth of its trade, local workshops for paper production emerged, though initially rudimentary. It was only after the construction of the first paper mill in the imperial capital, Baghdad, in 794–795, that paper was produced throughout the Islamic world and began to replace papyrus as the medium for transferring knowledge. This development was decisive for the dissemination of information and facilitated the spread of Islam into territories distant from its points of origin.

The manufacture of paper further strengthened the distribution and promotion of the Qur'an, as well as works of science, medicine, and literature; from the ninth century onwards it was regularly employed for book production. The advancement of papermaking techniques led to the multiplication of books and the establishment of public libraries already from the early eleventh century. Workshops producing paper from hemp and linen existed in Samarkand, Damascus, and especially in the new Abbasid capital, Baghdad,[2] which rivalled Byzantium in beauty and power until the mid-thirteenth century; it was reputed to be the richest city in the world and the greatest centre of intellectual activity of the period, with a population exceeding one million.

The revolution of hemp-based paper was fundamental in increasing the production of texts that contributed to the development of the Islamic Golden Age. The technology of hemp papermaking was thus transmitted throughout the Islamic world and subsequently to Europe.

Arabic paper reached Europe only at the beginning of the eleventh century, imported from Damascus via Constantinople, from Africa through Sicily, and also from western Morocco into Spain. The first rudimentary Spanish paper mill was established in 1009 near Córdoba, while the first more organised production centre was in the Valencian territory of Xàtiva in 1150. Initially, it was regarded as an inferior and unreliable material, of low durability and quality compared to parchment; in Sicily, an edict of 1221 issued at the court of King Crimson, Frederick II Hohenstaufen, prohibited its use for public documents of high importance. At the same time, however, Frederick II, called stupor mundi, clearly supported the use of paper for private writing and secondary administrative documents: his own chancellery issued mandates and maintained registers on paper.

Despite initial resistance, given the vast difference in costs, availability, and production time, the use and consumption of paper continued to increase, owing to its overall economic advantage. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the merchant fleets of the Mediterranean and Adriatic, financed by major traders—largely Venetian and Genoese—divided the prosperous market (Hoberman, 1982, p. 30).

All this technological and cultural capital made possible the cartographic explosion in Europe in the fifteenth century. It was not merely an increase in production, but a qualitative transformation that decisively reshaped the organisation of texts and codices and the representation of space.

Alessandro Bellucci

Hoberman, B., The Battle of Talas, Saudi Aramco World, 1982, pp. 26–31.; Hyunhee, P., Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds: Cross-Cultural Exchange in Pre-Modern Asia, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 25–26.; Bloch, M., La società feudale, B. M. Cremonesi (trans.), Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi, Nuova serie, Edizione 1, 1999.; Biran, M., Khitan Migrations in Inner Asia, Central Eurasian Studies, 2012, pp. 85–108.; Broc, N., La geografia del Rinascimento. Cosmografi, cartografi, viaggiatori: 1420–1620, Franco Cosimo Panini, 1996.

Explanatory Notes:

[1] Canapa. In China, papermaking techniques were a state secret, mastered only in certain workshops and by some Buddhist monks. In Central Asia, within regions of Chinese cultural heritage, high-quality paper had been produced and traded for centuries. According to many Chinese historians, paper made from plant fibres was invented in 105 CE by an imperial official, though recent archaeological findings demonstrate its use in China at least two centuries earlier. The new material was manufactured from rags and plant fibres derived from hemp, bamboo, mulberry, willow, etc. Its use was disseminated by Buddhist monks across many eastern countries (Biran, 2012, pp. 85–108).

Ancient Greeks cultivated hemp and used it for fabrics, ropes, and textiles of all kinds, as well as for medicinal purposes and to induce mild well-being. During the Middle Ages, cannabis cultivation continued in Greece, though it became limited due to subsequent wars and long-term occupation by Franks, Venetians, and eventually the Ottomans. The Romans also made extensive use of hemp in their cannabetum—fields cultivated with hemp across the Italian peninsula—processed mainly for ropes, cords, and various textiles. Pliny the Elder catalogued its qualities, noting particularly the fibres of Rosea (near present-day Rieti) and Miletus in Calabria. The same uses applied in the medieval Islamic world (Pisanti, S.; Bifulco, M., Medical Cannabis: A plurimillennial history of an evergreen, J. Cell. Physiol., 2019;234:8342–8351. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27725; Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Book 19, Paras. 61–65).

[2] Baghdad. The new city was strategically located along major trade routes on the Tigris River, with proximity to water ensuring a constant supply. Designed as a perfect circle with four walls, four gates facing the cardinal points, and a central mosque, it followed Persian-Sassanid urban planning traditions and the Platonic model of Atlantis. Founded north of the ancient cities of Ctesiphon and Babylon, it was named Madinat al-Salaam (“City of Peace”), although locals continued to use the pre-existing settlement name, Baghdad.

The city’s location and the investments made fostered commercial activity, cultural curiosity, and a cosmopolitan population, rendering it a central hub for trade, business, and learning, evidenced by the numerous Arab scholars who studied and conducted research there between the eighth and thirteenth centuries (Deroche, R., Richard, 1998, pp. 183–197).

Baghdad reached its cultural peak with the establishment of the Bayt al-Ḥikma (House of Wisdom), one of the most important institutions of the Arab world, a centre for the study and research of the humanities, sciences, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, zoology, and geography, and a major node in the translation movement of Greek and Persian texts into Arabic. Baghdad also hosted the first Islamic observatory, constructed in 828 CE (Al-Khalili, 2011, pp. 79–92; Bosworth, 1980, pp. 1–21; Biran, 2012, pp. 97–100; Hyunhee, 2012, pp. 25–26; Hoberman, 1982, p. 27; Al-Khalili, 2011, pp. 79–92).

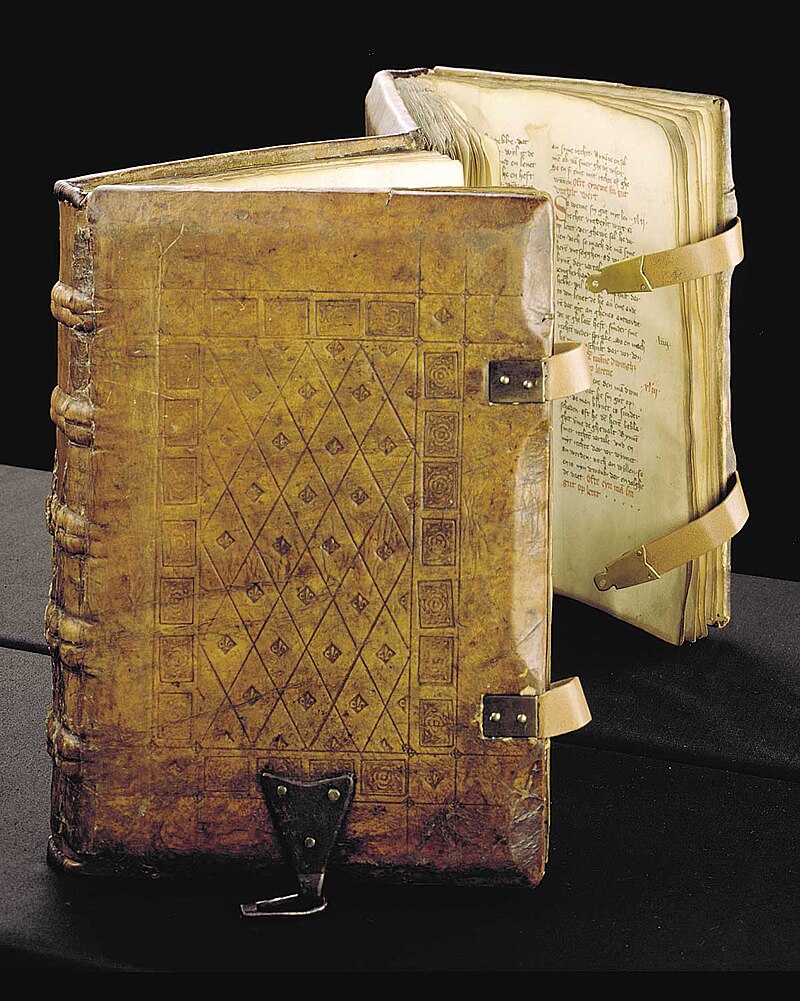

The first image shows a map of the city of Baghdad around 800 AD, with its typical circular structure. Next are the incipit of a manuscript of the Decameron (ca. 1420), the Gutenberg Bible (ca. 1450), and the American Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776). All three documents were produced on hemp and hemp-linen blend paper, the most durable and widespread type from the Middle Ages until the 19th century.

(The four images are from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia).

Brief mention of the Parchment

According to many scholars of the fifteenth century, among them O. P. Kristeller[1], the definition of humanist was adopted within the student jargon of the universities of the Italian peninsula of that period to designate those who devoted themselves to the studia humanitatis. This term thus referred to a specific university curriculum encompassing a range of disciplines, including grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, history, and moral philosophy, all of which were closely connected with the reading of Latin and Greek classical authors.

The books they handled and the sources to which they had access took forms and structures that changed over the centuries. The book of classical antiquity was known as the volumen (from the Latin volvere, "to roll" or "to unroll"): a sheet of papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) rolled into a scroll, a writing medium obtained by transforming the stalks of this plant into a flexible and smooth surface, several metres in length. The ancient book was constructed as a papyrus roll, composed of several strips, precisely cut and glued end to end; writing was arranged in parallel columns and generally only on the recto, that is, on the front face and not on the verso, the back. The text was contained on the inner side, since papyrus could be written on only one face, and reading required the use of both hands, unrolling from one side and rolling from the other (Deroche, Francis, 1998, pp. 183–197). This was the book of antiquity.

In addition to papyrus, parchment was also used as a writing support, a practice that spread in the second century BCE from Pergamon, in north-western Anatolia, where this material came into particularly wide use following the Egyptian prohibition on the export of papyrus (Giraudo, 2019, p. 53). This retaliation followed the decision of Eumenes II, king of Pergamon, to establish a cultural centre intended to rival that of Alexandria. Unlike papyrus, parchment—also known as charta pergamena or cartapecora—is a membrane made from treated calf, sheep, or goat skin. It has a more manageable structure and can be folded much more easily.

Written on papyrus rolls or on parchment, books in antiquity became the primary vehicle of culture. The demand for books developed above all in Athens in the first century BCE, where the first private collections emerged (Hodges, 1964, p. 149). Notable among these were those of the tragedian Euripides and the philosopher Aristotle, while others were established by the founders of medical or philosophical schools. A true book trade, however, developed in Rome around the first century BCE. From this period onward, the first publisher-booksellers appeared, mostly freedmen, who ran tabernae librariae in which books were produced and sold (ibid., p. 150).

Between the first and second centuries CE, the roll was progressively accompanied and then replaced by the codex, composed of folded sheets of papyrus or parchment gathered into quires and sewn along the fold. The sheets were written in one or two columns, not only on the recto but also on the verso, that is, on the back, thereby allowing a greater quantity of text.

After the barbarian invasions, in addition to a renewal in the religious sphere, from the end of the eleventh century Europe also experienced a period of economic, social, and cultural revival, with inevitable repercussions on law. The prevailing system, largely based on custom, Lombard law codes, and Carolingian capitularies, proved increasingly incapable of serving a society that was becoming more complex by the day.

Parchment was recovered thanks to the cultural revival initiated under the Carolingian Empire, inexorably replacing papyrus, which had become difficult to obtain and therefore very expensive. In the effort to enrich libraries with ancient and classical texts, the principal institutional structures that hosted this process of codification gradually took shape: monasteries, within which were the scriptoria, the workshops of the copyists, alongside other laboratories. Preparing parchment was a process that lasted several months, as the skin had to be washed with quicklime, scraped, and then cut in order to obtain sheets of uniform dimensions.

Small ruling lines were then drawn, on which the copyist wrote the text; subsequently the manuscript was rubricated, divided into chapters, an operation entrusted in book workshops to a specialised scribe known as the rubricator. Initially, these headings were indicated in red (from the Latin ruber), from which the term to rubricate is derived (Giraudo, 2019, p. 53).

If a sheet of parchment is folded once, it yields two leaves and four pages, the so-called folio; if folded twice, it produces four leaves, the so-called quarto format. Folding it three times produces eight leaves, a smaller format known as octavo. Folding it four times creates even smaller gatherings, known as sextodecimo.

When several gatherings are sewn together, the result is a codex. The codex can contain an enormous number of pages, enclosed between two boards, initially made of wood and later of lighter materials (cloth, leather, and so forth). Inside, the amount of content could be very substantial. On the spine of the codex the subject was written, allowing it to be shelved together with other codices.

Compared with the volumen, the codex had four fundamental advantages: (1) it did not require the use of both hands and therefore allowed multiple books to be consulted simply by leaving them open; (2) it permitted writing on both sides of the page, a crucial advantage in an age when writing materials were scarce; (3) it was easier to identify and to store; and (4) above all, it made it possible to interrupt reading at a specific point—by means, for example, of a bookmark—and then resume from that point without having to unroll the entire text, as was necessary with papyrus (Hodges, 1964, p. 148). This represented a significant form of modernisation.

From the fourteenth century onward, however, paper progressively replaced parchment. Cheaper and quicker to produce, paper enabled a far more rapid dissemination of texts and knowledge, relegating parchment to a slow and inexorable decline

[1] On Humanism, in the very broad and heterogeneous bibliography, some of the authors I went to consult on the subject: GARIN, 1978, pp. 25-29; KRISTELLER, 1965, pp. 5-10; GIACONE, 1974, Fasc. 1/2, pp. 58-72; BARNEY, 2006, p. 39; SAPORI, 1981, pp. 9-35; RONCHEY S., 2002, pp. 129-140; CAMMAROSANO, 2018, pp. 389.

Avant-Garde Humanists

Members and representatives of a category that the Polish historian Leszek Kołakowski (1) defined as "Christians without a Church" were the enterprising avant-garde humanists.

To be situated between the late fourteenth and the early fifteenth century, the Florentines Coluccio Salutati, Niccolò Niccoli, Palla di Nofri Strozzi, and Cosimo de' Medici, among others—all men of deep religiosity yet not integrated into the institutional and doctrinal system of the Church of their time—were the first to perceive the spirit of this new cultural movement.

Florence at the Time

After the economic and social disruption of the mid-fourteenth century—caused by banking failures, the Black Death, famine, and violent civil संघर्ष—culminating in the Ciompi Revolt of 1378, Florence embarked upon a recovery by reopening the public building projects that had been interrupted within the city. At the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, the decoration of the Porta della Mandorla was begun in 1391, and in 1398 the decoration of the external niches of Orsanmichele by the Arti commenced. In 1401 the competition for the north door of the Baptistery was announced.

This recovery, however, was overshadowed by the threat posed by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, who had encircled Florence as part of his project to create a national state in Italy under the dominion of Milan. On the other hand, the Florentines were more determined than ever to preserve their independence, sustained by a strong civic pride that appealed to the historic motto of Libertas.

With the sudden death of Visconti in 1402, the military pressure on the city was eased, allowing for economic recovery. In 1406 Pisa was conquered, and in 1421 the castle, the small town, and the port of Livorno were purchased from the Res Publica Ianuensis of Genoa.

The philosophical and cultural spirit of the period remained fundamentally scholastic, yet new currents were in motion: a renewed interest in Latin and Greek texts, and a growing attention to the concrete problems of civic life and knowledge. Emancipation from theological dominance also entailed the rediscovery of a practical approach to learning and understanding, and a freer, more independent mode of action.

(to be continued)

(1) Leszek Kołakowski, Editore Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2021, p. 662; Christians without a church. ....See Dictionary of Philosophy, 2009 and cf. GARIN, 1994, pp. 25-49; KRISTELLER, 2005; PELLEGRINI, 2012, pp. 149-160; FIORENTINO, 2016, pp. 552; MULLER, 2012, pp. 382; for William of Occam see DE GRUYTER, 2010, pp. 21-182; CAMPANINI, 2007 and for Scotus Duns see FIORENTINO F. Città Nuova, 2016.

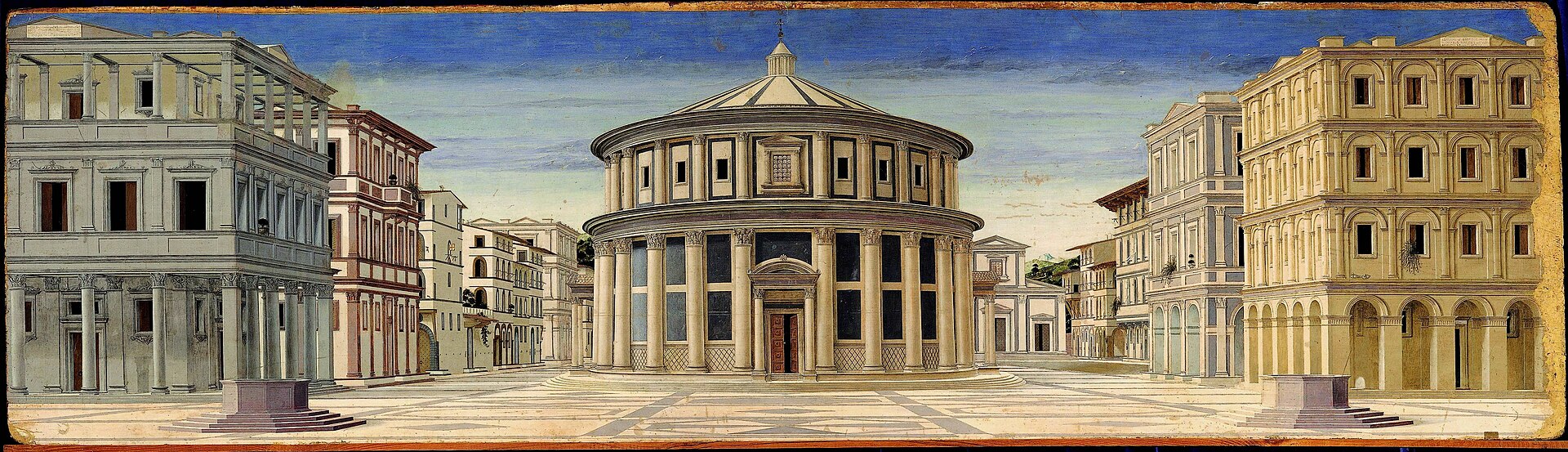

Città ideale

CONSTANTINOPLE

"Up to that time, there had remained there the living memory of ancient wisdom; and, as though it were the abode of letters themselves, no man of the Latin world could be deemed adequately learned unless he had spent a certain period studying in Constantinople.".

(Card. E. S. Piccolomini, letter to N. Cusano, 21 luglio 1453)*

Between Europe and Asia, on the Golden Horn—the inlet where ships of every size gathered—lay the epicentre of the world at that time, both for trade and for exchanges and encounters among different cultures: Byzantium.

The foundation of Constantinople, the city to which Constantine gave his own name, may justifiably be regarded as an epoch-making event, the outcome of a decision of exceptional magnitude, dense with implications and meanings (Dagron, 1987), taken in the aftermath of the defeat of his rival Licinius at Chrysopolis on 18 September 324 CE.

In Constantine's intentions, now sole ruler of the Empire, the new city—which he sought to assimilate to and equate institutionally with ancient Rome—was, beyond representing a new political centre in the pars orientalis of the Empire and a dynastic capital, to be configured as the monumental reflection of the glory of the basileus. As such it was conceived and planned, giving shape to an urban phenomenon of extraordinary scale [1]. Few other city foundations possess comparable historical importance (Ronchey, 2002; Ostrogorsky, 1967; Beck, 1994; Lilie, 2003; Runciman, Sir S., 1977; Ravegnani, 2004). The ambitious project began to take form only a few weeks after the definitive victory at Chrysopolis.

The architectural structure of the fourth-century vestibule is not known; however, from Eusebius of Caesarea's Vita Constantini (Eusebius of Caesarea, Life of Constantine, III, 3) we learn that at the entrance to the Palace the emperor had placed, high up and exposed to the view of all, an encaustic panel [2] in which he—surmounted by the 'saving sign', perhaps a labarum, and accompanied by his sons, Constantine and Constantius—was depicted piercing and casting into the depths of the sea a serpent in the form of a dragon, possibly Licinius, in an emblematic Christian reinterpretation of the traditional iconographic theme of the calcatio [3].

The presence of the Christian symbol—which, in an even more conspicuous form, also adorned, as Eusebius again writes, the ceiling of "the hall that surpasses all others in splendour" (Eus., V.C. III, 49) within the Palace—fits coherently within the framework of Constantine's political theology: the 'symbols', the cross and the chrismon—the monogram of Christ, or Chi-Rho—which had secured him victory, had become the phylacteries of kingship and also the talismans of the dynasty of the second Flavians.

From this perspective, the presence, alongside the encaustic panel, of a simulacrum of Tyche (Týchē), the personification of good fortune (Τύχη), the divinity of Greek mythology who guaranteed the prosperity of a city and its destiny (the Roman equivalent being the goddess Fortuna), a paradigm of the polis's fortunate fate (Dagron, 1987, p. 131), is therefore not surprising. It constituted another image of strong prophylactic value, albeit pagan, ubiquitous in the urban furnishings of the new capital, to which, by analogy with Roman Flora, Constantine had attributed the hieratic name Anthousa (Ανθουσα), that is, 'Florid'.

Tyche thus became a fundamental component of the conceptual fabric of the monumental decoration of Constantinian Constantinople: her simulacra were in fact 'strategically' placed at the most sensitive points of the new capital [4], visually establishing a line of continuity with the traditions of Rome and implicitly transferring their symbolic values to Constantinople.

The figure of Tyche is moreover widely present on the dies of contemporary coin issues, among them a silver multiple minted by the city's own mint in 330 CE [5]. On the obverse it bears the profile of Constantine with the gem-studded diadem, first worn as early as 324 CE on the occasion of the ceremonies for the foundation of the new capital; on the reverse stands the image of Tyche–Anthousa (Τύχη ᾿Ανθουσα), represented according to the traditional scheme, with veiled head covered by a modius [6], seated on a throne with a high back, holding a cornucopia and with her foot resting on the prow of a ship, signifying the city's maritime vocation [7].

Luca Drolles Bisance

Excerpt from the letter of Enea Silvio Piccolomini (1405–1464), elected Pope under the name Pius II on 19 August 1458, to Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa, 21 July 1453, two months after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks; see Pertusi, 1990, pp. 53–55.

[1] Cf. Becatti, 1959, pp. 886–914; Janin, 1964; Muller-Wiener, 1977; Meyer, 2002, pp. 91–174; Mango, 2004; for more recent summaries, see Franchetti Pardo, 2008, pp. 13–38; Schreiner, 2009; Berger, 2011.

[2] Encaustic (Gr. ἔγκαυστον, énkafston, from ἐν "in" and καίω "I burn"; Lat. encaustum) is a painting technique used by the ancients in which pigments were mixed with hot wax, heated at the moment of application; sometimes the wax was used together with oil. Cf. Venturini Papari, Encausto, Treccani, Enciclopedia Italiana (1932).

[3] Calcatio (ritual trampling, also known in Latin as calcatio colli or in Greek as trachelismos) is an ancient ritual, common in triumphal and ceremonial art, denoting the total submission of a defeated enemy. The vanquished enemy prostrates or lies on the ground before the victorious ruler, who symbolically tramples the enemy's neck (collis, trachelos). For a fuller understanding of the meaning of the image under discussion, see the suggestions of Prof. Barsanti: cf. Mango, 2004, pp. 23–24; Dagron, 1987, pp. 390–391; Krautheimer, 1987, pp. 76–77; De' Maffei, 2011, pp. 191–228.

[4] For the role attributed to Tyche (Τύχη) in Constantinian mysticism and for her effigies, cf. Dagron, 1987, pp. 40–47, 373–374; Kazhdan, Constantin Imaginaire, 1987, pp. 45, 47, 68, 90, 131, 185.

[5] Cf. Dagron, 1987, p. 33; Bardill, pp. 13–15. For reflections on the coinage of the Constantinople mint and the dies of Constantine, see also Dagron, 1987, pp. 49–51.

[6] Modius – a type of headdress or crown, cylindrical with a flat top; for further details, cf. Sebesta, Bonfante, 2001, p. 24.

[7] Cf. Buhl, 1995; Barsanti, 2013, pp. 471–475, with decisive notes on p. 486. For the descriptio of the city's foundation, see the sublime pen of the Byzantinist Prof. Claudia Barsanti, excerpted for the Treccani Institute: Barsanti, Rome, 2013, p. 471 with notes pp. 484–486. For definitions of polis and civitas, see also the introduction by the Italian philosopher and academic Umberto Curi, Alle radici dell'idea di città: la polis e la civitas, La Rivista, 2018.

See also: Manners, I. R., "Constructing the Image of a City: The Representation of Constantinople in Christopher Buondelmonti's Liber Insularum Archipelagi," University of Texas, Austin, 2004, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 87, 1997, pp. 72–102; Barsanti, C., Constantinople, excerpt, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana fondata da Giovanni Treccani, Rome, 2013, pp. 471–491; Ronchey, S., Lo Stato bizantino, Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi, Turin, 2002; Ravegnani, G., La storia di Bisanzio, Il Timone Bibliografico 3, Jouvence, 2004.

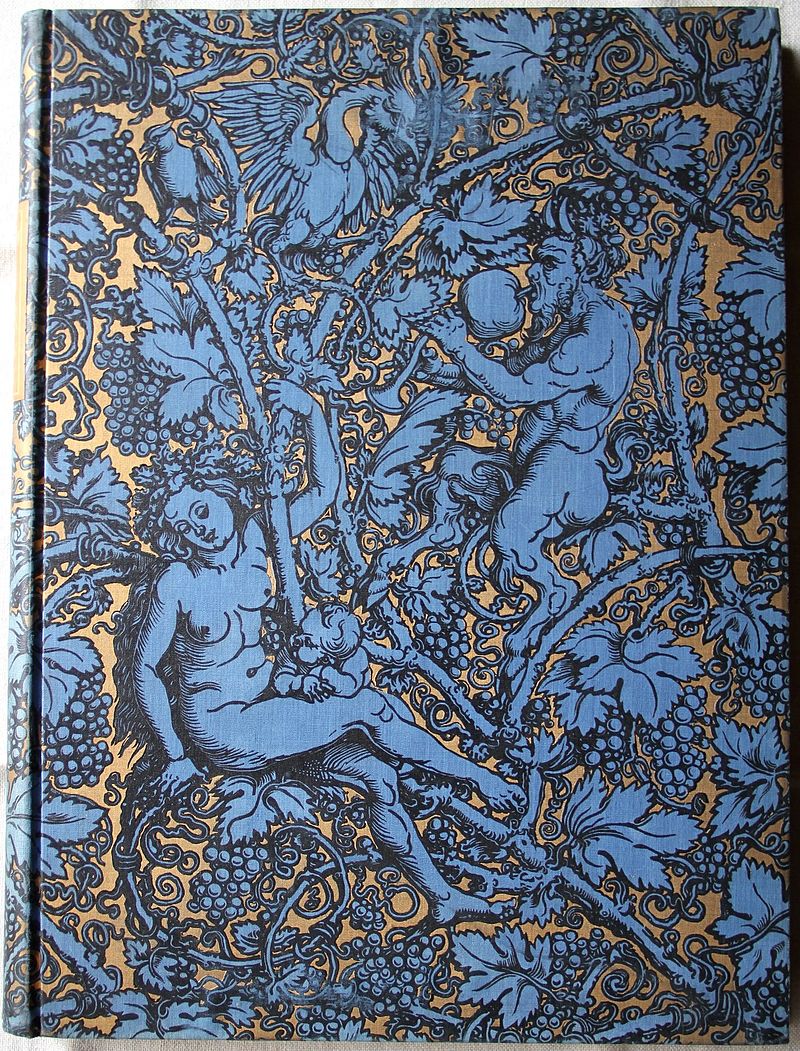

The Florentine engraving from the series Mercury of the Planets (c. 1460), originating from the workshop of Mario Vinciguerra (1426–1464), Salerno Editrice, Rome 1981; Baccio Baldini, The Planets, compiled by Laura Aldovini, 2011, Pavia (PV), Musei Civici di Pavia.

"This engraving forms part of a series of seven prints depicting the Planets according to ancient cosmography. Executed in a refined manner, they are attributed to Baccio Baldini and are considered among the earliest works produced by him (they were previously attributed to Maso Finiguerra). The compositions are divided into two sections: in the upper part the planet is shown advancing on a chariot drawn by animals symbolically associated with it, while in the lower part the human activities promoted by the planet that influences them are represented. The text in the lower margin describes the nature of the planet and of its 'children', as well as the time the planet requires to traverse the constellations. The iconography merges transalpine prototypes with distinctly Florentine elements, such as those derived from Boccaccio's Genealogiae deorum gentilium, together with clear references to the customs and practices of Medicean Florence.

The series enjoyed considerable success, to the extent that a second edition was produced in a reduced format (to which, as an eighth plate, the Almanac is associated, of which a modern pen-and-ink copy is preserved in the Malaspina Collection; cf. inv. St. Mal. 1560, OA record). The series preserved in Pavia (inv. St. Mal. 1585–1591) belongs to the first edition; it was purchased by Marquis Malaspina in 1812 from Abbot Mauro Boni (cf. Vicini 2000), and according to Hind constitutes the best-preserved exemplar among those known today.

The plate under consideration depicts Mercury, dressed in the antique manner, holding the caduceus and wearing winged sandals, seated on a chariot drawn by two falcons. On the wheels of the chariot are represented Virgo, the planet's diurnal domicile, and Sagittarius (in place of Gemini), as its nocturnal domicile. In the urban view below, Florentine buildings have been identified: the Palazzo della Signoria, the Loggia dei Lanzi, and the church of San Pier Scheraggio."

www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/stampe/schede/F0130-00295/

"Yet the creative power of the mind is capable of producing the wonder of what has never been seen before, and yet is plausible and governed by definite rules."

(L.B. Alberti, De re æd.)

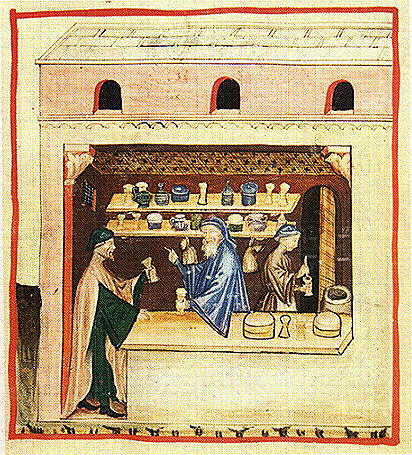

Medicine and Remedies in the Fifteenth Century

Between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, European medical knowledge was organised according primarily to the tradition set forth by Galen (129–c. 216 CE) and Avicenna (980–1037 CE).

From the Roman physician derived the physiological and therapeutic framework based on the humours and bodily balance (hot, cold, dry, moist), a sort of internal compass with which to interpret every ailment. This principle remained the foundation of diagnosis and remedies at least until the mid-seventeenth century.

The Arab physician Avicenna, by contrast, offered a broader, almost encyclopaedic perspective, which brought together clinical practice, drugs, air, seasons, and even celestial influences. Any illness was interpreted as the product of corrupt air, adverse astral conjunctions, or environmental imbalances that undermined the entire organism. Therapy consisted of a combination of advice on air, diet, and daily behaviour, considered as integral to the cure as pharmaceutical prescriptions.

The Black Death, which decimated roughly one quarter of the European population, was studied within these theoretical categories, justifying miasmatic explanations, dietary prescriptions, hygiene rules, and pharmacological remedies derived from scholastic medicine and hospital practice. Medical knowledge was exclusively academic, transmitted through commentaries, compendia, and lectures; a stable system in which the authority of the ancients weighed more heavily than direct observation.

Nevertheless, physicians, through Consilia, Regimina, compendia, and numerous recipe collections, combined scholastic tradition, practical observation, and hygienic prudence, seeking as never before to modernise and add to established knowledge. Within this framework, certain choices and many oddities, daring formulas, and improbable remedies can be understood.

Medieval medicine thus displayed its most creative and audacious side: a laboratory of ingenuity in which science, tradition, folly, vision, and the ridiculous coexisted in comic harmony.

Compendium, Consilium e Regimina

Breviaries, Opinions, and Rules Against the Black Death, 1348–1475: Popular Reactions and Medical Efforts

Giovanni Dondi: Bloodletting, Aromatics, and Fragrant Fires

In his Consilium against the Black Death, Giovanni Dondi (Chioggia 1330 – Abbiategrasso 1388), physician, astronomer, poet, and clockmaker, recommended bloodletting even on the patient's head, in order to reduce the infected blood of the body. Ablution of the face and hands with rose water and vinegar was considered obvious. Mists and fogs were to be avoided, as was the south wind. Dondi advised exposure, early in the morning, to the smoke of a well-scented fire, obtained from oak, ash, olive, or myrtle wood. The addition of balm, incense, or sandalwood to the flame was believed to enhance its disinfecting action. All foods were to be flavoured with strongly scented substances. Veal, goat, castrated mutton, partridge, pheasant, and chicken were considered safe, whereas fish—particularly freshwater species—was regarded as dangerous. Wine and beer were expressly recommended, while sweet fruits, such as pears, which spoil easily, were to be avoided (Gabrielli, 1984, p. 96).

Dionisio Colle: Berries, Bark, and Natural Remedies

Dionisio Colle of Belluno advised his fellow townsmen, as both prophylaxis and therapy, a natural remedy containing peach blossoms, lesser centaury, and clubmoss, combined with sugar and nectar. He also praised the efficacy of elderberry juice and euphorbia plants, diluted in goat's milk. In addition, he advocated the anti-miasmatic action of aromatic substances. It was therefore recommended to keep in the mouth berries of laurel and juniper, or even better, the bark of larch, pine, and fir (Ivi, 1984, p. 96).

Tommaso del Garbo and the Ancient Panaceas

Tommaso del Garbo, a Florentine (1305–1370), magister of medicine at Perugia and Bologna, from 1368 served in Milan and Pavia as court physician to Galeazzo II Visconti, which afforded him Francesco Petrarca among his patients. In his manual for protection against contagion, he recommended sprinkling interiors with cloves, whose scent, according to his experience, possessed a disinfecting effect. According to del Garbo's Consilium, sweet foods, preserved in fresh water and mixed with stimulating substances such as hawthorn, lemon balm, and sugar, were also considered effective, although, in his view, timely flight represented the best prophylactic measure (Gabrielli, 1984, p. 97). In the manner of Galen, he also exhorted those who could to consume bread dipped in wine, accompanied by the support of ancient panaceas such as theriac and mithridate.

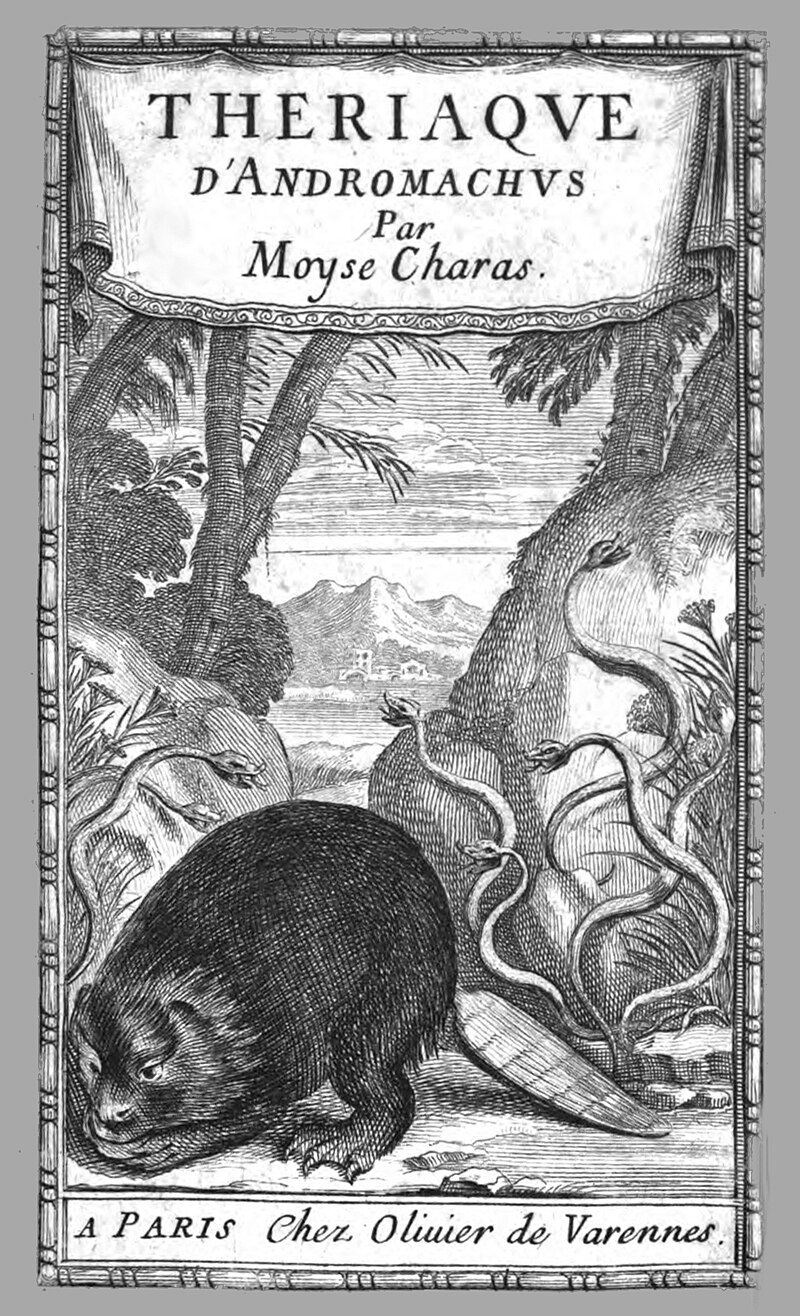

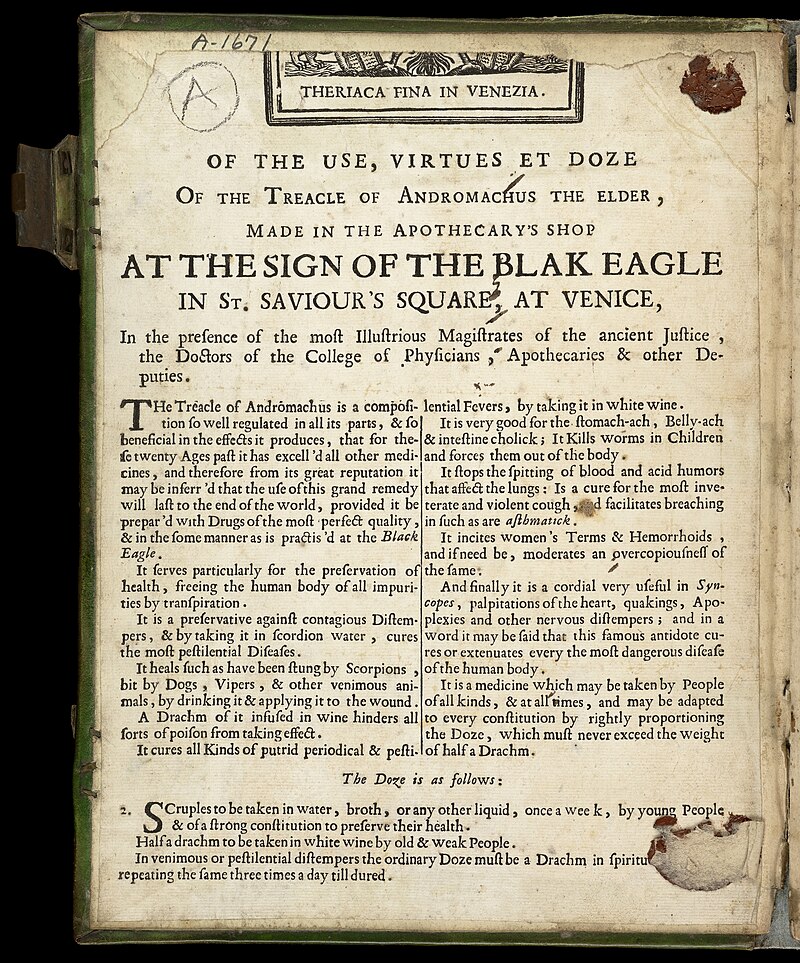

Theriac and Mithridate: Elixirs of Legend

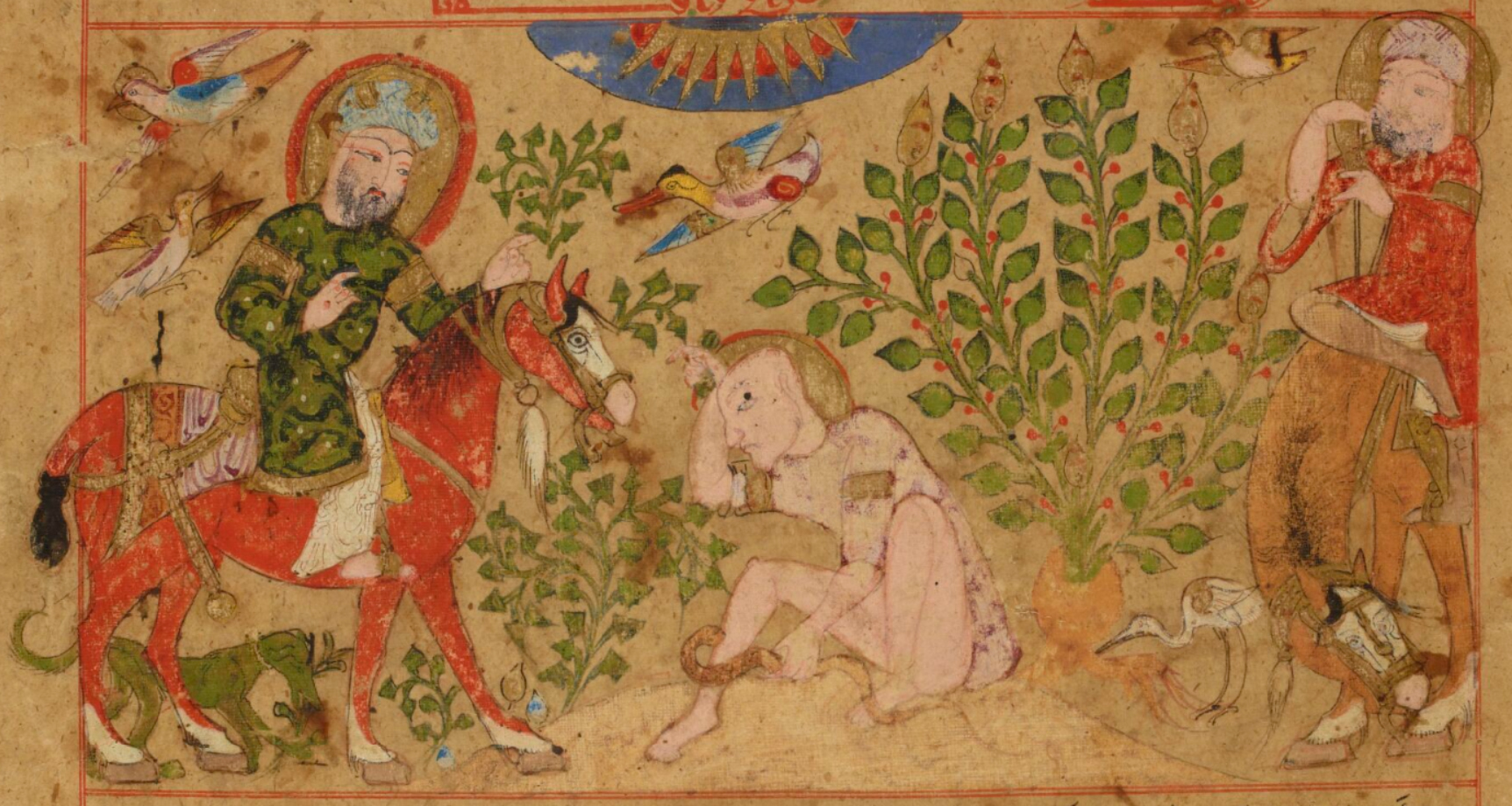

Theriac (from Lat. theriăcus adj., theriăca f., Gr. θηριακή thēriakḗ, that is, therapy, antidote) was a medicine of very ancient origin, with a preparation and composition of considerable complexity. Its fundamental base, despite the variations in formulas over the centuries, consisted of both the serum and the flesh of the viper (Lat. draco, Gr. δράκων drakōn – "snake"), believed capable of combating the "poisons" produced within the human body by disease, alleviating ailments of the stomach, head, sight, and hearing, promoting sleep, and invigorating and prolonging life. According to the axiom, the very poisons of viper, hemlock, or arsenic, if ingested in gradually increasing doses up to the threshold of lethality, would provoke the organism to generate antibodies, which, over time, would enrich the bodily structure with a habitus, a reactive mechanism against poisons, recognising their identity and neutralising their effects, rendering one immune and invulnerable to veneficium (Debus, 1997, pp. 43–44).

This formulary fired the imagination and desire of many, and the demand for such elixirs enjoyed a period of particular popularity during the medieval and Renaissance eras. The minimum prophylactic dose of theriac consisted of a daily quantity equivalent to the size of a hazelnut.

The methods of administration and dosage of theriac (as it was more commonly called) varied according to the disease, the age, and the degree of debilitation of the patient. The principal condition for its efficacy was that it be ingested after purging the body; otherwise, according to legend, the remedy would be worse than the disease. For maximum potency, the preparation was to rest for six years according to some, twelve according to others. It was considered active and efficacious up to the thirty-fifth year, gradually losing its benefit, and entirely inert fifty years after its production.

Among the ingredients of this polypharmacy were, from the vegetable kingdom, benzoin resin, myrrh, cinnamon, saffron, gentian root, gum arabic, incense, rhubarb, hemp, pitch, and opium. As animal components, in addition to viper flesh, some recipes included the flesh of other animals. Viper flesh was prepared by boiling in salted water flavoured with dill, cleaning out the entrails, and removing head and tail. After cooking, when the flesh separated from the bones, it was drained, mixed with finely ground dry bread, kneaded by hand, and divided into small portions, shaped into round pills as described in the ancient formulary: formed into coils, called trochischi by the Greeks and pastilli by the Latins, and then dried in the shade (Florentine formulary of physicians and apothecaries; Caprino, 2011, pp. 64–65).

From the Middle East to Europe: The Theriacs of Jerusalem

In the Holy Land, this preparation was well known and was exported to the West as early as the tenth century. Muhammad ibn Sa'id al-Tamimi (Jerusalem – c. 990) was an Arab physician, pharmacist, and arboriculturist of the tenth century, decisively influenced by De materia medica, the work of the ancient Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides, who lived in the first century. This was the first extensive documented treatise, comprising five books, which described approximately one thousand natural drugs (mostly plant-based), 4,740 medicinal uses, and 360 medical properties (analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiseptic, etc.). It served as a precursor to the modern pharmacopeia and was one of the most influential treatises on medicinal herbs in history, in use until the seventeenth century (Minta Collins, Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions, The British Library and University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2000).

In addition to his celebrated Guide to the Fundamental Principles of Nutrition and the Properties of Simple Drugs, al-Tamimi devoted himself to other important medical works, including several treatises on theriac. He is reported to have possessed extensive medical knowledge and excelled in the preparation of ointments and complex remedies, reaching the height of his prestige in combining the various ingredients of theriacs. The Jewish physician and rabbi Maimonides (Cordova 1135 – Cairo 1204) extensively used and cited al-Tamimi's works.

Numerous testimonies, all dating to the tenth century, indicate that one of the most important centres of theriac production in the Islamic world was Jerusalem. Its surroundings also provided a source for the individual components of theriac. A significant portion of the medicinal ingredients (plants, animals, and minerals) came from the Jerusalem area, primarily the Dead Sea basin, which was connected to Jerusalem administratively, economically, and culturally. Among the important components of theriac, in addition to opium, were raw mineral pitch from Tiberias and the flesh and serums of rattlesnakes hunted for this purpose in the Dead Sea region. Felix Fabri (1434–1502), a Swiss Dominican theologian, wrote that, due to the high demand for venom, Egyptian sultans often prohibited the hunting of snakes in the area to prevent their extinction.

The production and use of theriac in Jerusalem are mentioned in many writings, with direct testimony, notably from the Crusader kings Amalric (reigned 1162–1174) and Baldwin IV (1161–1185).

This trade and production continued: for example, in the eighteenth century, the recipe was mentioned in testamentary certificates assessing the assets of Jews who owned pharmacies. In the mid-nineteenth century, the Swiss physician Titus Tobler testified that theriac was still found in Jewish pharmacies in Jerusalem (Book Review: Zohar Amar and Efraim Lev, Arabian Drugs in Early Medieval Mediterranean Medicine, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018).

This potent medicine is said to have been devised by Andromachus the Elder, physician to Nero (first century CE), who described its recipe (De Theriaca) in verses of praise, so that, through meter and rhyme, the proportions of the doses would be more easily retained by the preparer. The Roman physician likely elaborated it based on Mithridate's universal antidote (Caprino, 2011, p. 64), a panacea for all ills.

Mithridatium and Pliny the Elder: Between Science and Art

Mithridate's antidote (also known as mithridatium, mithridatum, or mithridaticum) is a legendary elixir of antiquity, reputed as a universal antidote against poisons. It is said to have been created by Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus, in the first century BCE, a ruler remembered as one of the most formidable adversaries of the Roman Republic, who compelled it to wage three wars against him, engaging three of Rome's greatest generals—Sulla, Lucullus, and Pompey the Great—for nearly forty years. According to tradition, this mythical king fortified his body against poisons through antidotes and remedies such that, when he attempted suicide to avoid capture by his invincible enemy, he could find no poison effective, and was forced to ask a soldier to kill him with a sword.

The mithridatum, which took its name from him, was among the most complex and sought-after compounds throughout the Middle Ages, particularly in Italy and France, where it was used continuously for centuries (Mastrocinque, 1999, Intro; Appianus, pp. 111–115).

Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BCE – c. 45 CE), learned encyclopaedist and Roman physician, who treated both practical and theoretical disciplines in his treatise De Medicina, recorded a formulation of "Mithridatium" based on his data, precisely defined in terms of weight, comprising thirty-six ingredients, all plant-based except for honey, used as a medium, and castor oil, employed to enhance the aroma. The mixture is estimated to have weighed approximately three Roman pounds (1 L/R = 327.168 g), a quantity sufficient for about six months when taken in small portions. The antidote described by Celsus included, among other ingredients: acacia juice, cardamom, opium, anise, dried rose leaves, cinnamon, Cretan carrots, zizania, parsley, ivy, poppy seeds, amber resin, incense resin, ginger, rhubarb, and saffron.

Gaius Plinius Secundus, better known as Pliny the Elder (born at Como in 23 CE; died 24 August 79 CE at Stabiae from the fumes of Vesuvius during its famous eruption), writer, naturalist, philosopher, and naval and military commander of the early Roman Empire, and friend of Emperor Vespasian, famously stated: "True glory is to do what is worth writing, and to write what is worth reading." Pliny authored Naturalis Historia, an encyclopaedic series of investigations into natural phenomena, which became an exemplary model for works spanning extensive fields of knowledge.

The author from Como encountered further versions of this recipe, with even more ingredients, some provocative, others bordering on the sarcastic. To illustrate the elixir's efficacy, he wrote: "The Mithridatic antidote is composed of fifty-four ingredients, none of which are of equal weight, while some are prescribed in a sixtieth part of a denarius. Which of the gods, in the name of Truth, established these absurd proportions? No human mind could have been sufficiently astute. It is clearly a striking display of art and a colossal boast of science" (Grouth, Mithridatum, Encyclopaedia Romana).

Gentile da Foligno: Gold, Precious Stones, and Dietary Precepts

Gentile da Foligno, a distinguished teacher whose pupils included, among others, Tommaso del Garbo, was a profound scholar of Greek and Arabic medicine. He was active in Perugia and himself a victim of the bubonic plague in Foligno on 28 June 1348, exposing himself directly to care for the afflicted.

Gentile composed three different treatises on the plague: one, extensive, addressed to the citizens of Perugia; a second directed to prominent individuals in Perugia, offering personalized advice; and a third for the city of Genoa. In his Tractatus de pestilentia et causis eius et remediis (1348), addressed to the physicians of Genoa, he emphasized that all food should be moistened with wine, and aromatic substances employed: camphor for hot meals and selaginella for cold meals, to restore health to the affected area. Acidic foods were considered optimal nourishment, while bloodletting and isolation of the sick were prescribed as the foundations of therapy against the plague.

The Folignate physician, a proponent of theriaca as the primary therapeutic remedy, aware that certain components were inaccessible to many due to scarcity or cost, prescribed for the poor a formula substituting rare herbs and spices with more readily available ones, together with various practical precautions.

To those who could afford it, Gentile recommended, depending on the progression of the plague, first purging the body of poisoned humours, and then administering cordial preparations—intended to strengthen the heart, the organ most affected by noxious vapours. Such cordial preparations included ingredients such as gold, rare pearls, and precious stones. Gentile may also have been the first to suggest a composition akin to a syrup of rose water (distilled rose water, already well known and employed by the Salernitan school), into which a gold rod was repeatedly immersed until the solution assumed the colour of gold. In the absence of gold, a gold coin, such as a florin, could be used; if the patient could afford it, this potion or true potable gold, for which Gentile provides a recipe, could be administered, rendered "cordialissimum," that is, highly efficacious in sustaining the heart.

Following Avicenna's methodical advice in the Canon medicinae, where the Persian physician suggested pulverising and mixing certain precious stones (Gabrielli, 1984, p. 95), Gentile employed, in addition to gold, combinations such as pearls, karabé (amber), and coral as a basis for heart-strengthening and as the primary amalgam for preparing cold-quality medicines; silver and jade powders were also among the most frequently prescribed ingredients in these formulations.

Avicenna and Galen: The Theoretical Framework

Plague medicine in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was still grounded in the models of Galen and Avicenna: the theory of the humours, the qualities of the air, astral causes, and dietary regulations.

The Consilia and Regimina against the Black Death of 1348 represented the first preventive and curative manuals in the West, and in the case of the Regimina, they consisted primarily of dietary prescriptions addressed both to physicians and to laypersons. The earliest Consilia were conceived in continuity with the theories of Galen and Avicenna (Benedicenti, Milan, 1947, I, p. 314), although these ancient authorities did not aim at true innovation: their primary purpose was to recognise, restate, and enumerate the knowledge received from the past.

This perspective invites reflection on the level of medical arts, knowledge, and limitations of the period, and on the manner in which such knowledge adapted in response to an event of such magnitude (Winslow, Duran-Reynals, 1948, pp. 747–765).

During and after the Great Plague of 1348, physicians were chiefly concerned with determining which element within the various Consilia might prove the most potent.

Gold was among the principal candidates, due to its value and exclusivity, as the metal most capable of acting within the body and expelling the poison that was attacking the heart, according to the humoural theory proposed by Avicenna (Crisciani C., 2014).

In the second book of his Canon medicinae, Avicenna defines gold as a cordial remedy, that is, one which supports the heart. By a series of analogies and prevailing beliefs, the heart was considered the centre of the organism and, according to Aristotelian theory, the principal member of the body; in turn, gold was regarded as the highest and most perfect of metals. Furthermore, gold possesses an extremely temperate structure, that is, a perfectly balanced constitution, and was therefore deemed capable of imparting this same equilibrium to the organs to which it was applied (Avicenna, Canon medicinae). Among the criticisms we might raise today is, for example, that minerals are not digestible.

Giovanni da Rupescissa: The Visionary Franciscan

The friar who decisively pursued the path to gold was Giovanni da Rupescissa (Jean de Roquetaillade; Marcolès, c. 1310–Avignon, 1365), an Occitan with modest medical competence but considerable alchemical knowledge. One of his codices, the Liber lucis, is renowned: an alchemical text in which he set forth the procedure that would enable the transmutation of both lead and the basest metals into gold—a procedure of utterly preposterous implausibility when read with modern eyes, yet one that stirred debate at the time.

Proclaiming and declaring himself a prophet, he was an apocalyptic thinker who raved about numbers and dates concerning the end of the world and the advent of the Antichrist, that menacing figure heralding the 'last times', as announced also by the Dominican Vincenzo Ferreri and many other catastrophists thereafter throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. A Spiritual Franciscan who took as his reference the most extremist wing of pauperistic Franciscanism, he was long imprisoned in various French gaols, not so much for heretical scientific theses as for reasons of religious order.

Perpetually incarcerated in sundry French towns, accused of dialectical ravings but implicitly indicted and charged with proximity to the 'beghinism' line and minor currents circulating in those regions—currents branded as 'heretical' owing to their exclusively literal interpretation of the Holy Scriptures, theses in turn influenced by the teachings of the Albigensians (Cathars)—it is thus at least permissible to suspect that the true motive for Rupescissa's incarceration, and above all the aversion of his superiors towards him, is to be sought more in his positions on poverty and obedience than in his prophetic and visionary activity.

Giovanni, whom his contemporaries dubbed a phantasticus (a term akin to: visionary, chimerical, somewhat mad), was nonetheless no unwitting deliriant. He also authored a text, De consideratione quintae essentiae, in which he programmatically declared his intent to present remedies for the poor—that is, for the pauperes Christi, whom he regarded as both the evangelical poor, to whose ranks the Frenchman adhered, and more generally the simple poor, who could not access costly medicines.

The Franciscan proffers a recipe employing all the ingredients deemed effective in treatises against the plague, among them the quintessence of gold—though in this instance rendered accessible even to the poor. The monk indeed provides instructions on how to prepare, in a sort of bucket, the quintessence, which is none other than modern-day aquavitae, that is, wine-water distilled many times over, endowed thus with intense heat, potent activity, and an exceedingly high alcoholic content. To this is added gold, specially processed to be incorporated into this alcoholic solution. 'Even the poor may benefit therefrom: they shall borrow—suggests the Phantasticus—some coins, insert them into this most potent aquavitae solution, which by its strength will capture the virtues of the gold and not its materiality, that is, the qualities by which gold is an incorruptible metal. This done, the poor man may return the coin he has used, identical as before, vel quasi.'

This aurified product of his is akin to that described by Gentile da Foligno, but the preparation is more detailed: it entails, as a first stage, the distillation of the aquavitae (brandy), then the use of the aquavitae as a vessel for the gold, and finally the availability of an aurified fiery water, that is, endowed with the powers of gold or the sun: an excellent remedy against both leprosy and plague. Thus does the Franciscan conjoin these two tragic maladies, to be cured by a single remedy.

The distillation of waters is no novelty in either Arabic or Latin pharmacology: here it is augmented by the fortification of aqua fortis through the incorporation and infusion of transformed gold. A liquid extract prepared at highest potency, which Giovanni da Rupescissa described as thaumaturgic: 'it is marvellous and stupendous, of instantaneous effect, utterly exceptional, and possessed of an indescribable fragrance; it is no miracle, though some may deem it such, for the potency of this aurified aquavitae makes the dead rise again. For— he specifies—I do not say that it resurrects the truly dead, but sustains the moribund, those on their final passage, since a small sip of this most potent cordial revives them marvellously, so that they may perform the last acts no longer expected of them, namely receiving the sacraments and making their testament.' (CRISCIANI C., 2014).

Giovanni della Penna and the Angevin Studium. Electuaries, Precious Stones, and the Heart as the Centre of the Organism

The contribution of the medical faculty of the Angevin studium of Naples also enjoyed considerable renown, especially that of Giovanni della Penna*, the celebrated physician who taught there from 1344 to 1387.

The use of precious stones as fundamental ingredients in the preparation of specific electuaries, along with dietary and medical precepts, was advocated by the Neapolitan professor, who not only reiterated preventive and curative measures such as avoidance of the sick, blood purification through purges and bloodletting, and indications regarding diet and physical activity, but also furnished an elaborate recipe for an electuary to be taken before and after meals, in which figured amber, corals, emeralds, and crystals.

Administered after the patient had contracted the disease, these had the purpose of fortifying the heart. He particularly recommended a medicine based on rose water, sugar, coriander, sandalwood, and cinnamon, «to which it is possible also to mix precious stones» precisely in order to augment its effect of confortatio upon the heart.

Oftentimes, when precious stones appeared in relation to materia medica, they did so in the form of amulets, that is, not to be ingested but rather hung about the neck or wrist (MARASCHI, 2020, cit. pp. 1-35); more rarely were they reduced to powder—almost certainly on account of their intrinsic value—and administered orally (WEILL-PAROT N., 2004, pp. 77-78).

The thesis of Giovanni della Penna, by virtue of his rejection of the precepts of astrological medicine, influenced the thought of important chroniclers of the age, among them Giovanni Boccaccio, known at the Angevin court. Notwithstanding that the Neapolitan physician accepted that the cause of such humoral corruption arose from miasmic air, he held that not all were subject to the effects of pestilential air in equal measure; rather, it devolved upon the individual person and their specific, personal humoral balance whether they might fall victim to the Black Death. The originality of his treatise lay also in his critique of certain contemporaries who vaunted truths concerning the universal causes of the pestilence. Among these, he expressly named ignorant and incompetent physicians (imperiti) and—more generically—the fools (ydeoti) who believed the disease to proceed from God or from the stars.

.The Legacy of the Consilia

The transmission of Greek sciences by Avicenna, and the translation of his works into Latin—as well as those of other less renowned Arab physicians—provoked the first scientific awakening in southern Europe, a revival that began in Sicily in the twelfth century, thence extending to Salerno, Toledo, Barcelona, and Paris, ascending as far as northern Europe. The influence of the Persian physician is thus evident, both directly upon prestigious teachers and physicians such as the Catalan Jacme d'Agramont, Giovanni della Penna, the Medical Faculty of Paris, or Gentile da Foligno, and indirectly upon charlatans, improvised physicians, or self-taught alchemists such as Jean de Roquetaillade.

Only in the course of the sixteenth century did the situation begin to evolve. Prior to that turning point, the accredited theories for explaining the epidemic were substantially two: the miasmatic theory and the contagionist theory, which for a long time set university physicians against public authorities. The former, by far the majority view and also known as the aerist or anti-contagionist theory, emphasized the role of the air which, once corrupted and altered, was responsible for transporting and diffusing toxic miasmas; it posited that plague was not contagious. The latter, in opposition, circumscribed the causes of the disease's diffusion to interpersonal contagion proper, through proximity and contact.

Only towards the end of the eighteenth century would a new scientific method begin to assert itself, and it would be necessary to await the final decades of the nineteenth century in order definitively to identify the cause of the Black Death epidemic (GIOVANNI DELLA PENNA, Tractatus, cit., p. 164; A. MONTGOMERY CAMPBELL, The Black Death and Men of Learning, New York, Columbia University Press, 1931, p. 38 and pp. 90-91; GIOVANNI DELLA PENNA, Consilium contra pestem, cit., p. 346).

Luca Droller Bisance

____________________________________________

Cfr. CAPRINO L., Il Farmaco, 7000 anni di storia, dal rimedio empirico alle biotecnologie, Armando Editore, Roma, 2011, pp. 64-99; GABRIELLI F., La peste nera, in Les épidémies de l'homme, ed. ROUFFIE' J., SOURNIA J.C., Storica National Geographic, Flammarion, Paris, 1984, pp. 94-97; COSMACINI G., Storia della medicina e della sanità in Italia. Dalla peste nera ai giorni nostri, Laterza, Roma-Bari, 2016; BENEDICENTI A., Malati, medici e farmacisti. Storia dei rimedi traverso i secoli e delle teorie che ne spiegano l'azione sull'organismo, 2 vols., Hoepli, Milano, 1947; MAHADIZADEH S., KHALEGHI GHADIRI M., GORJI A., 'Avicenna's Canon of Medicine: a review of analgesics and anti-inflammatory substances', Avicenna J Phytomed, 2015; 5 (3), pp. 182-202, in National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information; TUCHMAN B., Uno specchio lontano. Un secolo di avventure e di calamità. Il Trecento, trans. PARONI G., Milano, Mondadori, 1979, p. 774; Mark Grant, La dieta di Galeno. L'alimentazione degli antichi romani, trans. Alessio Rosoldi, Ed. Mediterranee, Roma, 2005.